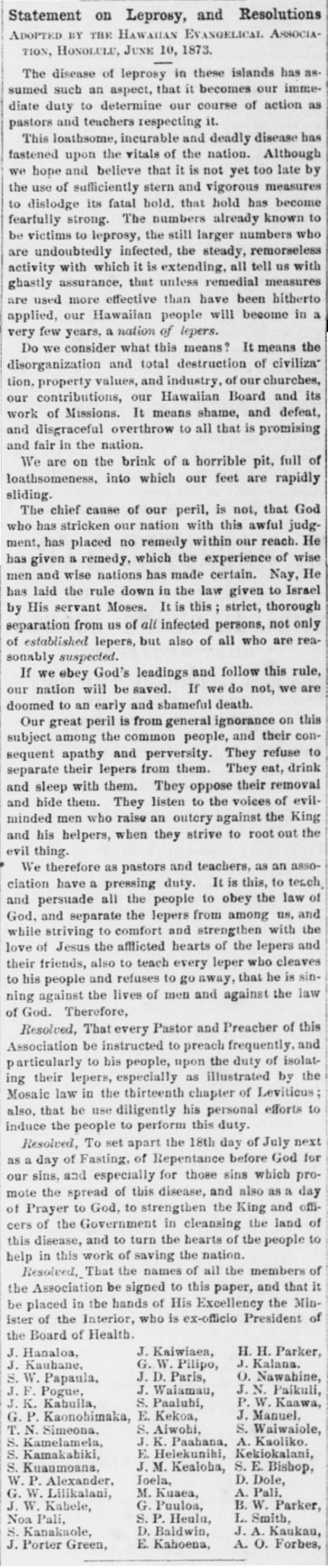

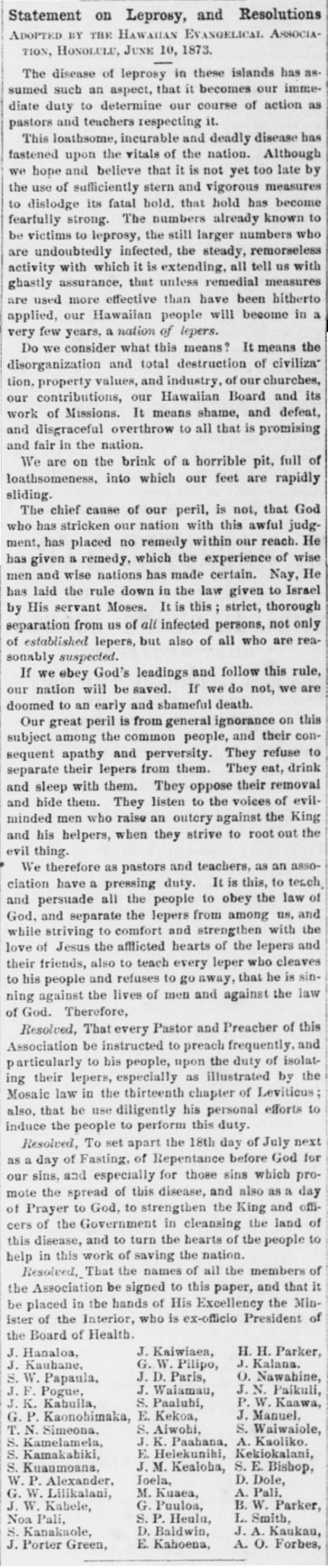

Statement on Leprosy, and Resolutions

Adopted by the Hawaiian Evangelical Association, Honolulu, June 10, 1873.

The disease of leprosy in these islands has assumed such an aspect, that it becomes our immediate duty to determine our course of action as pastors and teachers respecting it.

This loathsome, incurable and deadly disease has fastened upon the vitals of the nation. Although we hope and believe that it is not yet too late by the use of sufficiently stern and vigorous measures to dislodge its fatal hold, that hold has become fearfully strong. The numbers already known to be victims to leprosy, the still larger numbers who are undoubtedly infected, the steady, remorseless activity with which it is extending, all tell us with ghastly assurance, that unless remedial measures are used more effective than have been hitherto applied, our Hawaiian people will become in a very few years, a nation of lepers.

Do we consider what this means? It means the disorganization and total destruction of civilization, property values, and industry, of our churches, our contributions, our Hawaiian Board and its work of Missions. It means shame, and defeat, and disgraceful overthrow to all that is promising and fair in the nation.

We are on the brink of a horrible pit, full of loathsomeness, into which our feet are rapidly sliding.

The chief cause of our peril, is not, that God who has stricken our nation with this awful judgment, has placed no remedy within our reach. He has given a remedy, which the experience of wise men and wise nations has made certain. Nay, He has laid the rule down in the law given to Israel by His servant Moses. It is this; strict, thorough separation from us of all infected persons, not only of established lepers, but also of all who are reasonably suspected.

If we obey God’s leadings and follow this rule, our nation will be saved. If we do not, we are doomed to an early and shameful death.

Our great peril is from general ignorance on this subject among the common people, and their consequent apathy and perversity. They refuse to separate their lepers from them. They eat, drink and sleep with them. They oppose their removal and hide them. They listen to the voices of evil-minded men who raise an outcry against the King and his helpers, when they strive to root out the evil thing.

We therefore as pastors and teachers, as an association have a pressing duty. It is this, to teach and persuade all the people to obey the law of God, and separate the lepers from among us, and while striving to comfort and strengthen with the love of Jesus the afflicted hearts of the lepers and their friends, also to teach every leper who cleaves to his people and refuses to go away, that he is sinning against the lives of men and against the law of God. Therefore,

Resolved, That every Pastor and Preacher of this Association be instructed to preach frequently, and particularly to his people, upon the duty of isolating their lepers, especially as illustrated by the Mosaic law in the thirteenth chapter of Leviticus; also, that he use diligently his personal efforts to induce the people to perform this duty.

Resolved, To set apart the 18th day of July next as a day of Fasting, of Repentance before God for our sins, and especially for those sins which promote the spread of this disease, and also as a day of Prayer to God, to strengthen the King and officers of the Government in cleansing the land of this disease, and to turn the hearts of the people to help in this work of saving the nation.

Resolved, That the names of all the members of the Association be signed to this paper, and that it be placed in the hands of His Excellency the Minister of the Interior, who is ex-officio President of the Board of Health.

J. Hanaloa, J. Kaiwiaea, H. H. Parker,

J. Kauhane, G. W. Pilipo, J. Kalana,

S. W. Papaula, J. D. Paris, O. Nawahine,

J. F. Pogue, J. Waiamau, J. N. Paikuli,

J. K. Kahuila, S. Paaluhi, P. W. Kaawa,

G. P. Kaonohimaka, E. Kekoa, J. Manuel,

T. N. Simeona, S. Aiwohi, S. Waiwaiole,

S. Kamelamela, J. K. Paahana, A. Kaoliko,

S. Kamakahiki, E. Helekunihi, Kekiokalani,

S. Kuaumoana, J. M. Kealoha, S. E. Bishop,

W. P. Alexander, Ioela, D. Dole,

G. W. Lilikalani, M. Kuaea, A. Pali,

J. W. Kahele, G. Puuloa, B. W. Parker,

Noa Pali, S. P. Heulu, L. Smith,

S. Kanakaole, D. Baldwin, J. A. Kaukau,

J. Porter Green, E. Kahoena, A. O. Forbes.

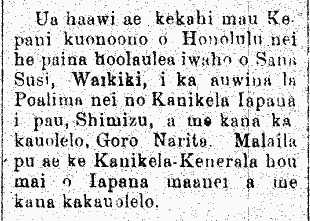

[How have things changed today? How have things remained the same? Find the Hawaiian-Language version printed in the Kuokoa, 6/18/1873, p. 3, here.]

(Pacific Commercial Advertiser, 6/14/1873, p. 3)

The Pacific Commercial Advertiser, Volume XVII, Number 50, Page 3. June 14, 1873.