HOKULEʻA SAILS AGAIN

Hold on to the course! Hold on to the course! Continue On!

by Wayne Washburn, Malcolm Naea Chun and Duke Wise

In early March the Hokuleʻa will again set sail in hopes of reaching first landfall somewhere near Tahiti. Crewmen and scientists will concentrate efforts on documenting the thinking process, and methods, which may have been used by the ancient Polynesian navigators.

Without first voyage demonstration to the modern world two important findings. First, was that navigation by the stars without use of modern navigational instruments can be successfully used when travelling between Tahiti and Hawaii. Second, a Polynesian double-hulled canoe without keels or deep centerboards is able to sail to windward, and thus maintain planned course. For the present voyage celestial navigation will once again be of primary importance. Where the first voyage showed that celestial navigation was possible, the presēnt will pay particular attention to the recording of the thought process of the navigator.

Dr. Will Kyselka of the Bishop Museum Planetarium, and an assistant to the project, cited an incident involving a highly skilled non-instrument navigator from Satawal, Mau Piailug. Once caught in a storm for three days, Mau was unable to sail or use celestial markers for assistance. After the storm, though his course direction had been turned around many times, Mau miraculously found his way home to his tiny atoll of Satawal. Dr. Kyselka suggested that maybe there are maps within some of the more skilled navigators’ minds. He mentioned that pigeons are said to find their bearings in flight by being able to sense the difference magnetic fields given off by certain structures. Using the changes in magnetic fields the pigeons are able to draw a mental map and find their way home. Did the Polynesians possess this ability or something which would enable them to find Tahiti and Hawaii with regularity?

Captaining the voyage down will be Gordon Piianaia. Navigating for the trip will be Nainoa Thompson. There to assist Thompson will be Mau Piailug, the navigator from the 1976 voyage. Crew member Steve Somsen will be documenting the navigation process. This will be done by conferring with Nainoa and Mau and then orally recording it through the use of a tape recorder. Hopefully this will shed more light on the Polynesians’ navigational thought process.

The Ishka, a sailing vessel captained by Alex Jackobenko with assistance from his wife Elsa will follow some distance behind Hokuleʻa. Dr. Kyselka will be on board to study and document the route of the Hokuleʻa using modern navigational instruments and charts. On completion of the voyage the two styles of navigation will be compared for scientific value.

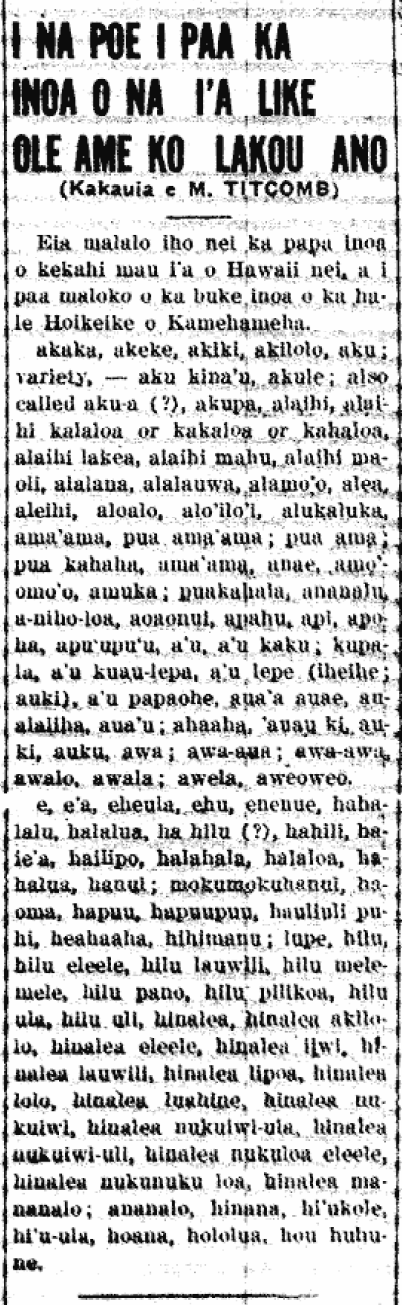

March has been designed for departure because it is the season that tends to favor the northeast tradewinds which are important for the first half of the voyage. Like the 1976 voyage the canoe will travel southeasterly for about 1000 miles. Once “easting” is accomplished winds blowing from the southeast will be used to rēach first landfall or Tahiti from a windward approach. This “easting” is important in that not enough movement in that direction might cause them to sail west of Tahiti and miss the islands completely. Certain safety features have been added to the canoe in order to avoid swamping problems encountered in previous inter-island trips. The gunwales and hatches have been raised to help prevent water seepage into the hulls. Also on board will be six hand pumps, a radio and flares. The radio will be used to notify the Hokuleʻa’s escort boat in case of an emergency. Certain sections of the hulls will contain inflated rubber. In the event that the hulls are accidentally smashed these will enable the canoe to remain afloat. Although non-instrumental navigation is the paramount research project of this voyage, other projects are being encouraged on a smaller scale. One of these is to fish using traditional types of fishhooks to learn how they were used. This hopefully will also provide a supplement to the crew’s diet by adding fresh fish. While conducting the fishing experiments crew members will record how the differences of fishhooks: design, material and size; the speed of the canoe; the types of fish caught and other factors affect fishing in the deep sea. These fishhooks are being faithfully copied from authentic fishhooks under the supervision of Sam Ka’ai of Kaanapali, Maui. Ancient fishhooks were made from materials such as shell, coral, turtle shell, dog and human bones and even hard woods.

In 1964, Drs. Kenneth Emory and Y. Sinoto of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, found a Tahitian one-piece fishhook at Maupiti in the Society Islands. They proposed a theory that this type of fishhook is the same as found in various sites in Hawaii. After its initial introduction they believe it became a major type used by the ancient Hawaiians, Today, other anthropologists are not as certain if Tahitian migrations caused the popularity of this fishhook, but nonetheless, the experiments conducted by crew members of the Hokuleʻa should provide some information that may help the on going research in finding common links between the ancient Hawaiian society and the Southern Polynesians.

With a crew of fourteen, the Hokuleʻa is scheduled to depart from Hilo on…

(Ke Alahou, 2-3/1980, p. 1)

Ke Alahou, Helu 4, Aoao 1. February/March 1980.

…the first favorable day after March 2.

Editor’s comment: The projects conducted by the crew of the Hokuleʻa remind us of the legend of Hema, a pan-Polynesian legend about a great super chief.

Hema was the son of Aikanaka and his wife Hinaaimalama of Hana, Maui. Hema’s wife was called Hina-polipoli and they lived at Kipahulu, East Maui. When she was pregnant with their second child, Hina craved for the eyeball of a large fish of the open, deep sea. This fish had a tail like that of the shark, Ahiale and was called Kekukaipaoa.

Hema prepared all his fishing gear and made ready the double-hulled canoe by loading enough food and water for several days. He covered his canoes with many mats, lashing them down with cords so that sea water could not seep in. When the canoe was covered securely, he hung his fishing line, Pupuwaiakolea, above the top of the poles that were between the hulls of the canoes. He put the end of the line through a knot he had tied and then he set up his cord calabash, which was called Kumaaiku. He took out the fishhook and tied the end of the fish line tightly around it fastening it to the pole.

Hema’s fishhook was not made of human bone like some of those found in the Bishop Museum, nor was it made of whale bone or turtle shell like Manaiakalani. It was made of a branch of wood whose name is not known today. The kikala or the intersection of the barbs, is found at the branch closest to the trunk of the tree. When this branch is laid flat, three other branches project from it. These branches are broken so they are short and sharp. This joint is called lehua, perhaps after the flower. The shank knob of the fishhook is called muʻo and this is where the fish line is tied. The name of Hema’s fishhook is Papalahoʻomau and still survives today as the name of the Congregational Church in Kipahulu.

It was later on in the story that Hema was blown off course and his voyage to Kahiki or Holani-ku began.

(Alahou, 2-3/1980, p. 11)

Ke Alahou, Helu 4, Aoao 11. February/March 1980.